Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic

| Република Советикэ Сочиалистэ Молдовеняскэ Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească (Moldovan) Молдавская Советская Социалистическая Республика (Russian) Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Capital | Chişinău/Kishinev | ||||

| Official language | Russian and Moldovan (de-facto)[1] | ||||

| Established In the Soviet Union: - Since - Until |

August 2, 1940 June 28, 1940 (90%); October 12, 1924 (10%) August 27, 1991 |

||||

| Area - Total - Water (%) |

Ranked 14th in the USSR 33,843 km² negligible |

||||

| Population - Total - Density |

Ranked 9th in the USSR 4,337,600 (1989) 128.2/km² |

||||

| Time zone | UTC + 3 | ||||

| Anthem | Anthem of Moldavian SSR | ||||

| Medals | |||||

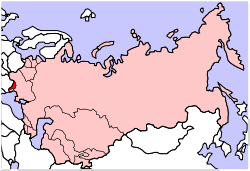

The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldovan/Romanian: Република Советикэ Сочиалистэ Молдовеняскэ or Republica Sovietică Socialistă Moldovenească; Russian: Молда́вская Сове́тская Социалисти́ческая Респу́блика Moldavskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika), commonly abbreviated to Moldavian SSR or MSSR, was one of the 15 republics of the Soviet Union. After the Declaration of Sovereignty on June 23, 1990, and until the Declaration of Independence on August 27, 1991, it was officially referred as Soviet Socialist Republic of Moldova, and since early 1991 as Republic of Moldova.

The Moldavian SSR was formed on August 2, 1940 from parts of Bessarabia, a region annexed from Romania on June 28th of that year, and MASSR, an autonomous republic within the Ukrainian SSR. It gained independence in 1991 as Republic of Moldova.

Contents |

History

Creation

After the failure of the Tatarbunar Uprising, the Soviets set up an autonomous Moldavian ASSR on October 12, 1924 within the Ukrainian SSR on part of the territory between the Dniester and Bug rivers, as a way to prop up the propaganda effort and help a potential Communist revolution in Romania.[2]

On August 24, 1939, the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany signed a 10-year non-aggression treaty, called the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact. The pact contained a secret protocol, revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945, according to which the states of Northern and Eastern Europe were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence".[3] The secret protocol placed the Romanian province of Bessarabia in the Soviet "sphere of influence."[3] Thereafter, both the Soviet Union and Germany invaded their respective portions of Poland,[4] while the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia in June 1940,[5][6] and waged war upon Finland (1939–1940).

On June 26, four days after France sued for an armistice with the Third Reich, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Romania, demanding the latter to cede Bessarabia and Bukovina.[7] After the Soviets agreed with Germany that they would limit their claims in Bukovina, which was outside the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact's secret protocols, to northern Bukovina, Germany urged Romania to accept the ultimatum, which Romania did two days later.[8] The Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was thereafter created following the entrance of Soviet troops on June 28, 1940.

The old Moldavian ASSR was dismantled and the Moldavian SSR was organized on August 2, 1940 from six full counties and small parts of three other counties of Bessarabia, and the six westernmost rayons of the Moldavian ASSR (about 40% of its territory).[9] 90% of the territory of MSSR was on the right bank of the river Dniester, which was the border between the USSR and Romania prior to 1940, and 10% on the left bank. Smaller northern and southern parts of the territories occupied by the Soviet Union in June 1940 (the current Chernivtsi Oblast and Budjak), which were more heterogeneous ethnically, were transferred to the Ukrainian SSR, although their population also included 337,000 Moldovans.[9] As such, the strategically important Black Sea coast and Danube frontage were given to the Ukrainian SSR, considered more reliable than the Moldavian SSR, which could have been claimed by Romania.[10]

In the summer of 1941, Romania joined Hitler's Axis in the invasion of the Soviet Union, recovering Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, as well as occupying the territory to the east of the Dniester it dubbed "Transnistria". By the end of World War II the Soviet Union had reconquered all of the lost territories, reestablishing Soviet authority there.

| History of Moldova | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Prehistory | |

| Antiquity | |

| Dacia | |

| Free Dacians | |

| Bastarnae | |

| Early Middle Ages | |

| Origin of the Romanians | |

| Tivertsi | |

| Brodnici | |

| Golden Horde | |

| Principality of Moldavia | |

| Foundation | |

| Stephen the Great | |

| Early Modern Era | |

| Phanariots | |

| United Principalities | |

| Bessarabia Governorate | |

| Treaty of Bucharest | |

| Moldavian Democratic Republic | |

| Sfatul Ţării | |

| Greater Romania | |

| Union of Bessarabia with Romania | |

| Moldavian ASSR | |

| Moldovenism | |

| Moldavian SSR | |

| Soviet occupation of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina | |

| Soviet deportations | |

| Republic of Moldova | |

| Independence of Moldova | |

| War of Transnistria | |

| Politics of Moldova | |

|

Moldova Portal |

Stalinist period: repressions and deportations

Many Bessarabians who fled to Romania before the advancing Red Army were eventually caught by Soviet security forces; a high percentage of these were shot or deported, blamed as collaborators of Romania and Nazi Germany.[11]

The Soviet authorities targeted several socio-economic groups due to their economic situation, political views, or ties to the former regime. They were deported to or resettled in Siberia and northern Kazakhstan; some were imprisoned or executed. According to a report by the Presidential Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Romania, no less than 86,604 people were arrested and deported in 1940-1941 alone. Modern Russian historians put forward an estimative number of 90,000 for the same period.[12] NKVD/MGB also struck at anti-Soviet groups, which were most active in 1944-1952. Anti-Soviet organizations such as Democratic Agrarian Party, Freedom Party, Democratic Union of Freedom, Arcaşii lui Ştefan, Vasile Lupu High School Group, Vocea Basarabiei were severely reprimanded and their leaders were persecuted.

A de-kulakisation campaign was directed towards the rich Moldavian peasant families, which were deported to Kazakhstan and Siberia as well. For instance, in just two days, July 6 and July 7, 1949, over 11,342 Moldavian families were deported by the order of the Minister of State Security, I. L. Mordovets under a plan named "Operation South".[11]

Religious persecutions during the Soviet occupation targeted numerous priests.[13] After the Soviet occupation, the religious life underwent a persecution similar to the one in Russia between the two World Wars.

Other deportation campaigns were directed towards the ethnic Germans (whose number decreased from over 81,000 in 1930 to under 4,000 in 1959 due to voluntary wartime migration and forced removal as collaborators after the war) and religious minorities (700 families, especially Jehovah's Witnesses, were deported to Siberia in April 1951 under the plan "Operation North").[11]

Stalinist period: collectivisation

Collectivisation was implemented between 1949 and 1950, although earlier attempts were made since 1946. During this time, a large-scale famine occurred: some sources give a minimum of 115,000 peasants who died of famine and related diseases between December 1946 and August 1947, others put the figure at 216,000, in addition to 350,000 related sickness cases. According to Charles King, there is ample evidence that it was caused by the Soviets and directed towards the largest ethnic group living in the countryside, the Moldovans. The main cause was the Soviet requisitioning of large amounts of agricultural products, but it was also aggravated by war, the draught of 1946, and collectivisation.[11]

Khrushchev Thaw: 1956-1964

With the regime of Nikita Khrushchev replacing that of Joseph Stalin, the survivors of Gulag camps and of the deportees were gradually allowed to return to the Moldovan SSR. The political thaw ended the unchecked power of the NKVD/MGB, and the centrally planned economy gave rise to development in the areas such as education, technology and science, health care, and industry (except in the fields that were considered politically sensitive, such as genetics or history).

Stagnation: 1964-1985

Between 1969 and 1971, a clandestine National Patriotic Front was established by several young intellectuals in Chişinău, totaling over 100 members, vowing to fight for the establishment of a Moldavian Democratic Republic, its secession from the Soviet Union and union with Romania. In December 1971, following an informative note from Ion Stănescu, the President of the Council of State Security of the Romanian Socialist Republic, to Yuri Andropov, the chief of KGB, three of the leaders of the National Patriotic Front, Alexandru Usatiuc-Bulgăr, Gheorghe Ghimpu and Valeriu Graur, as well as a fourth person, Alexandru Şoltoianu, the leader of a similar clandestine movement in northern Bukovina, were arrested and later sentenced to long prison terms.[14]

In the 1970s and 1980s Moldova received substantial investment from the budget of the USSR to develop industrial, scientific facilities, as well as housing. In 1971, the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a decision "About the measures for further development of Kishinev city" that secured more than one billion rubles of investment from the USSR budget[15] Subsequent decisions directed enormous wealth and brought highly qualified specialists from all over the USSR to develop the Soviet republic. Such an allocation of USSR assets was partially influenced by the fact that Leonid Brezhnev, the effective ruler of the USSR from 1964 to 1982, was the Communist Party First Secretary in the Moldavian SSR in 1950-1952. These alocations stopped in 1991 with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, when Moldova became independent.

Perestroika and the road to the independence: 1985-1991

Although Brezhnev and other CPM first secretaries were largely successful in suppressing Moldovan nationalism, Mikhail S. Gorbachev's administration facilitated the revival of the movement in the region. His policies of glasnost and perestroika created conditions in which national feelings could be openly expressed and in which the Soviet republics could consider reforms independently from the central government.

The MSSR's drive towards independence from the USSR was marked by civil strife as conservative activists in the east (especially in Tiraspol), as well as Communist party activists in Chişinău worked to keep the MSSR within the Soviet Union. The main success of the national movement in 1988-1989 was the adoption on August 31, 1989 by the Supreme Soviet of the Moldavian SSR of the Moldavian language as official, declaration in the preambule of a Moldavian-Romanian linguistic unity, and the return of the language to the pre-Soviet Latin alphabet. In 1990, when it became clear that Moldova was eventually going to secede, a group of pro-USSR activists in Gagauzia and Transnistria proclaimed independence in order to remain within the USSR. Gagauzia was eventually peacefully incorporated into Moldova as an autonomous territory, but relations with Transnistria soured.

Independence

On May 23, 1991, the Moldovan parliament changed the name of the republic from "Moldavian SSR" to "Republic of Moldova". Moldova then seceded from the USSR and became a sovereign, independent country on August 27, 1991, after the failed coup in the Soviet Union. Independence was quickly followed by civil war in the east of the country (Transnistria), where the central government in Chişinău battled with separatists, who were supported by pro-Soviet forces and by different forces from Russia. The conflict left the breakaway regime (Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic) in control of Transnistria.

Relationship with Communist Romania

In the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty, the Soviet Union and Romania reaffirmed each other's borders, recognizing Bessarabia, northern Bukovina and the Herza region as territory of the respective Soviet republics.[16]

Throughout the Cold War, the issue of Bessarabia remained largely dormant in Romania. In the 1950s, research on history and of Bessarabia was a banned subject in Romania, as the Romanian Communist Party tried to emphasise the links between the Romanians and Russians, the annexation being considered just a proof of Soviet Union's internationalism.[17]

Starting with the 1960s, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej and Nicolae Ceauşescu began a policy of distancing from the Soviet Union, but the debate over Bessarabia was discussed only in scholarship fields such as historiography and linguistics, not at a political level.[18]

As the Soviet-Romanian relations reached an all-time low in the mid-1960s, Soviet scholars published historical papers on the "Struggle of Unification of Bessarabia with the Soviet motherland" (Artiom Lazarev) and the "Development of the Moldovan language" (Nicolae Corlăţeanu). On the other side, the Romanian Academy published some notes by Karl Marx which talk about the "injustice" of the 1812 annexation of Bessarabia and Nicolae Ceauşescu in a 1965 speech quoted a letter by Friedrich Engels in which he criticized the Russian annexation, while in another 1966 speech, he denounced the pre-WWII calls of the Romanian Communist Party for the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia and Bukovina.[19]

The issue was brought to light whenever the relationships with the Soviets were waning, but never never became a serious subject of high-level negotiations in itself. As late as November 1989, as Russian support decreased, Ceauşescu brought up the Bessarabian question once again and denounced the Soviet invasion during the 14th Congress of the Romanian Communist Party.[20]

After the fall of communism in Romania, its president Ion Iliescu, and the president of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev have signed on April 5, 1991 a political treaty which among other things recognized the Soviet-Romanian border. However, Romania refused to ratify it. Romania and Russia eventually signed and ratified a treaty in 2003[21]a[›], after the independence of Moldova and Ukraine.

Organization and leadership

Communist Party

The Moldavian Communist Party was a component of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Communist Party was the sole legal political organization. It had supreme power in the land, as all state and public organizations were its subordinates.

| year\official ethnic group | Moldavians | Ukrainians | Russians | Jews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 6.3% | 31.6% | 41.6% | 15.7% |

| 1940 | 17.5% | 52.5% | 11.3% | 15.9% |

| 1989 | 47.8% | 20.7% | 22.2% | 2.5% |

| name | period | place of birth |

|---|---|---|

| Piotr Borodin | 1941–1942 | Ukraine |

| Nikita Salogor | 1942–1946 | Ukraine |

| Nicolae Coval | 1946 - July 1950 | Moldova (Camenca, Transnistria) |

| Leonid Brezhnev | July 1950 - October 1952 | Ukraine |

| Dimitri Gladki | October 1952 - 1954 | Ukraine |

| Zinovie Serdiuk | 1954 - May 1961 | Ukraine, Kherson Oblast |

| Ivan Bodiul | May 1961 - December 1980 | Ukraine, Mykolaiv Oblast |

| Semion Grossu | December 1980 - November 1989 | Ukraine (Sarata, South of Bessarabia) |

| Petru Lucinschi | November 1989 - February 1991 | Moldova (Bessarabia) |

| Grigore Eremei | February-August 1991 | Moldova (Bessarabia) |

Administrative subdivision

Until the 1978 Constitution of the Moldavian SSR (15 April 1978), the republic had four cities directly subordinated to the republican government: Chişinău, Bălţi, Bender, and Tiraspol. By the new constitution, the following cities were added to this category: Orhei, Rîbniţa, Soroca, and Ungheni.[26] The former 4 cities, and 40 raions were the first-tier administrative units of the land.

Economy

Agriculture

Although it was the most densely populated republic of the USSR, the Moldavian SSR was meant to be a rural country specialized in agriculture. Kyrgyzstan was the only Soviet Republic to hold a larger percentage of rural population.[27]

While holding just 0.2% of the Soviet territory, it accounted for 10% of the canned food production, 4.2% of its vegetables, 12.3% of its fruits and 8.2% of its wine production.[27]

Industry

At the same time, most of the Moldovan industry was built in Transnistria. While accounting for roughly 15% of the population of Moldavian SSR, Transnistria was responsible for 40% of its GDP and for 90% of electricity production.[28]

Major factories included the Rîbniţa steel mill, Dubăsari and Moldavskaia power station and the factories near Tiraspol, producing refrigerators, clothing and alcohol.[27]

Society

Ideology

The political elite of the Moldavian SSR was one of the most loyal among the Soviet Republics.[29]

Some towns and villages were renamed after various Communist leaders.

Education and language

Until 1952, the education for the locals was done in a very broken language (extremely low vocabulary and many borrowings from Russian and from the Soviet bureaucratic speech) that was spoken by a handful of ethnically Moldavian communist activists from the former Moldavian ASSR, and using the Cyrillic script. At that point, realizing that to create a whole literature for a speech shared by only a few hundred individuals and impose it on 3 millions was impossible, the Soviet authorities decided to drop it "because the local peasants cannot understand it", and return to the normal language. Hence, Mihai Eminescu and Ion Creangă were again allowed, and the standard written language became the same as Romanian, except that it was written with Cyrillic script.

The Soviet authorities policy of describing 1918-1940 period as a yoke of feudal boyars and rich bourgeois speaking in half-French assigned to the word Romanian a negative connotation. Locals' ethnicity was written as Moldavians in documents, and the language was renamed Moldavian language. In the Bukovinian part of the Chernivtsi oblast, locals did not have the habit of calling themselves both Moldavians and Romanians before 1918, as they did in Bessarabia, and hence the Soviet authorities allowed them to keep their ethnic group as Romanians in the documents. This also became handy, as split into Moldavians and Romanians , the share of the ethnic group in the population of the oblast was statistically less observable. Children of deportees that were prevented to return to Moldova from Siberia and Kazakhstan were allowed to be schooled only in Russian.

In Moldavian SSR, Soviet authorities opened many more Russian schools than Romanian ones in the cities, calling for locals to send their children to Russian-language schools, explaining them that without knowing Russian they would not be able to get normal jobs. Russian schools were also less crowded with respect to the number of students in a class. The authorities encouraged in addition the creation of mixed schools, generally having three Romanian-language for every Russian-language class, thus all administration being in Russian.

A new local intelligentsia, to replace the virtually exterminated one, started to form in late 1960s and early 1970s. However, being composed generally of descendants from farmers, it did not have the benefit of direct ties to the pre-war intelligentsia. The contacts with classical Romanian literature were greatly limited, as a big number of authors and books were forbidden, including all authors born in Romanian localities outside the medieval Principality of Moldavia, as well as all works touching on their connected to politics of even authors such as Mihai Eminescu, Mihail Kogălniceanu, Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, Constantin Stere (the former two are classic and well-known, the latter two are in addition born in Bessarabia). However, these contacts were not severed, since after 1956 people were slowly allowed to visit or get visits from relatives in Romania, since Romanian press could be freely bought in Moscow (not in Moldova), and since a poor quality Romanian TV and radio could be heard with a makeshift antenna, and even by ordinary transistor-based radios. The programs of the latter, however, were created by the Communist authorities of Romania, which never dared to cross the Soviet authorities, especially in the question of education and press for ethnic Romanians in USSR, which was a political taboo, especially because the Romanian communists did not totally sided with Soviets against the Chinese after 1959, sometimes even trying to play the brokers.

The Soviet-Romanian border along the Prut river, separating Bessarabia from Romania, was closed for the general public all throughout the Soviet era. In general, visits abroad by Soviet citizens were very rare (comparing to the citizens of Communist Eastern European countries).

In 1940, at the beginning of the Soviet occupation, the Capitoline Wolf, Chişinău was destroyed.

Culture

The little nationalism which existed in the Moldavian elite manifested itself in poems and articles in literary journals, before their authors being purged in campaigns against "anti-Soviet feelings" and "local nationalism" organized by Bodiul and Grossu.[29]

The official stance of the Soviet government was that Moldavian culture was distinct from Romanian culture, but they had a more coherent policy than the previous one from the Moldavian ASSR.[30] There were no more attempts in creating a Moldavian language that is different from Romanian, the literary Romanian written with the Cyrillic alphabet being accepted as the linguistic standard for Moldova, the only difference being in some technical terms borrowed from Russian.[31]

Moldavians were encouraged to adopt the Russian language, which was required for any leadership job (Russian was intended to be the language of interethnic communication in the Soviet Union). In the early years, political and academic positions were given to members of non-Moldavian ethnic groups (only 14% of the Moldavian SSR's political leaders were ethnic Moldavians in 1946), although this changed as time went on.

Literary critics stressed the Russian influence on Moldavian literature and ignored the parts shared with Romanian literature.

Demographics

Immigration

As the Soviet persecutions, as well as the grave reduction of the German, Jewish and Polish communities affected the local intelligentsia most of all, basically eradicating it, Soviet authorities sought to fill the intellectual gap formed in the region in 1940s, and also to build a Soviet and party apparatus. Immediately after the war, Stalin carried out a major colonization and de facto Russification campaign in what was now Soviet Moldova, Chernivtsi oblast, and Budjak under the flag of Sovietization. Many Russians and Ukrainians, along with a smaller number of other ethnic groups, who migrated from the rest of the USSR to Moldova, arrived to rebuild the heavily war-damaged economy. They were mostly factory and construction workers who settled in major urban areas, as well as military personnel stationed in the region. During the Soviet rule, up to one million people settled in Moldova. From a socio-economic point of view, this group was quite diverse: in addition to industrial and construction workers, as well as retired officers and soldiers of the Soviet army, it also included engineers, technicians, a handful of scientists, but mostly unqualified workers, or people without strong family or native land ties, many of which with little or no education at all.

Access of native Bessarabians to positions in administration and economy was limited, as they were considered also not trustworthy. The first local to became minister in the Moldavian SSR was only in 1960s as minister of health. The antagonism between "natives", and "newcomers" (cf. "venetici" in Romanian) persisted until the dissolution of the Soviet Union and was clear during the anti-Soviet and anti-Communist events in 1988-1992. It was also an important reason for the brief 1992 War of Transnistria. The immigration affected mostly the cities of Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, as well as the countryside of Budjak where the Bessarabian Germans previously were, but also the cities of Trasnistria. All of these saw the proportion of ethnic Moldavians (Romanians) drop throughout the Soviet rule.

Despite the immigration, the 1959 census showed a significant drop in population from 1940, showing how badly the local population was affected by the events of 1940-1956.

| ethnic group | 1941 | 1959 | 1970 | 1979 | 1989 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moldavians | 1,620,800 | 68.8% | 1,886,566 | 65.4% | 2,303,916 | 64.6% | 2,525,687 | 63.9% | 2,794,749 | 64.5% |

| Romanians | - | - | 1,663 | 0.06% | 1,581 | 1,657 | 2,477 | 0.06% | ||

| Ukrainians | 261 200 | 11.1% | 420,820 | 14.6% | 506,560 | 14.2% | 560,679 | 14.2% | 600,366 | 13.8% |

| Russians | 158,100 | 6.7% | 292,930 | 10.2% | 414,444 | 11.6% | 505,730 | 12.8% | 562,069 | 13.0% |

| Jews | - | - | 95,107 | 3.2% | 98,072 | 2.7% | 80,127 | 2.0% | 65,672 | 1.5% |

| Gagauz | 115,700 | 4.9% | 95,856 | 3.3% | 124,902 | 3.5% | 138,000 | 3.5% | 153,458 | 3.5% |

| Bulgarians | 177,700 | 7.5% | 61,652 | 2.1% | 73,776 | 2.1% | 80,665 | 2.0% | 88,419 | 2.0% |

| Gypsy | - | - | 7,265 | 0.2% | 9,235 | 0.2% | 10,666 | 0.3% | 11,571 | 0.3% |

| others | 23,200 | 1.0% | 22,618 | 0.8% | 43,768 | 1.1% | 48,202 | 1.2% | 56,579 | 1.3% |

| Total | 2,356,700 | 2,884,477 | 3,568,873 | 3,949,756 | 4,335,360 | |||||

Note: "-" means the official census data does not identify that group in that year, i.e. counts it within other groups, not that the group is not present.

Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship

The Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Moldova will study and analyze the 1917-1991 period of the communist regime.

Notes

- ↑ The Constitution did not define any official language, see Radio Free Europe report for details

- ↑ King, p.54

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Text of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact, executed August 23, 1939

- ↑ Roberts 2006, p. 43 & 82

- ↑ Wettig, Gerhard, Stalin and the Cold War in Europe, Rowman & Littlefield, Landham, Md, 2008, ISBN 0742555429, page 20-21

- ↑ Senn, Alfred Erich, Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above, Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 9789042022256

- ↑ Roberts 2006, p. 55

- ↑ Nekrich, Ulam & Freeze 1997, p. 181

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 King, p.94

- ↑ King, p.95

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 King, p.96

- ↑ Mikhail I. Semenga, Tainy Stalinskoi Diplomatii, Moskva, Vysshaya Shkola, 1992, p.270

- ↑ (Romanian)Martiri pentru Hristos, din România, în perioada regimului comunist, Editura Institutului Biblic şi de Misiune al Bisericii Ortodoxe Române, Bucureşti, 2007, pp.34–35

- ↑ Unionişti basarabeni, turnaţi de Securitate la KGB

- ↑ Architecture of Chişinău on Kishinev.info, Retrieved on 2008-10-12

- ↑ TREATY OF PEACE WITH ROUMANIA Part I, article 1. of "Australian Treaty Series" at the "Australasian Legal Information Institute" austlii.edu.au

- ↑ King, p.103

- ↑ King, p.103-104

- ↑ King, p.105

- ↑ King, p.106

- ↑ Armand Goşu, "Politica răsăriteană a României: 1990-2005", Contrafort, No 1 (135), January 2006

- ↑ E.S. Lazo, Moldavskaya partiynaya organizatsia v gody stroitelstva sotsializma(1924-1940), Chisinău, Ştiinţa, 1981, p. 38

- ↑ William Crowther, "Ethnicity and Participation in the Communist Party of Moldavia", in Journal of Soviet Nationalities I, no. 1990, p. 148-49.

- ↑ 1925 data refer to Moldavian ASSR

- ↑ Moldavian Soviet Encyclopedia, Chişinău, Glavnaia Redaktsia MSE, 1979

- ↑ "The New Constitution of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic", Radio Free Europe background report

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 King, p.99

- ↑ John Mackinlay and Peter Cross (editors), Regional Peacekeepers: The Paradox of Russian Peacekeeping, United Nations University Press, 2003, ISBN 92-808-1079-0 p. 135

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 King, p.99, 102

- ↑ King, p.107

- ↑ King, p.107-108

- ↑ V.V. Kembrovskiy, E.M. Zagorodnaya, "Naselenie soyuznyh respublik", Moscow, Statistika, 1977, p. 192

- ↑ Soviet 1959, 1970, 1979, and 1989 population censa.

References

- Charles King, The Moldovans: Romania, Russia, and the Politics of Culture, Hoover Institution Press, 2000

- Nekrich, Aleksandr Moiseevich; Ulam, Adam Bruno; Freeze, Gregory L. (1997), Pariahs, Partners, Predators: German-Soviet Relations, 1922-1941, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231106769

- Roberts, Geoffrey (2006), Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953, Yale University Press, ISBN 0300112041

External links

- THE NEW CONSTITUTION OF THE MOLDAVIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC by George Cioranescu and R. Flers

- Moldavia; a flourishing orchard by Aleksandr Diorditsa

- photogallery of the Kishinev (1950s-1980s) - the capital of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||